Should We Call Theology “Conservative”?

Rather than defining theology as liberal or conservative, it might be better to use other terms.

I love my mother-in-law’s deviled eggs. If we’re around while she’s making them, before she loads the heavenly filling into the boiled egg-whites, she’ll usually call one of us into the kitchen to taste it. We’ll tell her whether we think it needs more salt, more tang, or more “kick.” This reflection is a little like I’m whipping up something in the kitchen, and I want you to tell me if it “tastes right.” In other words, these are thoughts I’m still working on and working out. So please bear with me, and let me know what you think.

Lately, there’s been a lot of brouhaha in my neck of the evangelical Protestant woods about who the true “conservatives” are. For example, the “Conservative Baptist Network” (CBN) is a sort of factional group in the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC). The CBN aims to reclaim the network of the SBC from what some have claimed is a “liberal drift.” Rarely addressed in these discussions is an assumption sitting under the surface discourse: that “conservative” is basically synonymous with “faithful.” We (and I include myself in the “we”) use such language almost instinctively, that “Christians who believe the Bible” are “conservative.” Why is this, and is it the best way to talk about things?

Why “Conservative”?

“Conservative” came to describe Christian theology in part because those Christians opposed the emergence of theological “liberalism.” Liberalism broke through in the 19th century with the work of theologian Freidrich Schleiermacher. From Schleiermacher onward, Protestant Liberalism radically redefined Christianity and its doctrinal teaching. It was critical of the reliability and infallibility of the Bible. It taught that Jesus was not God and man but a man who was close to God. In contrast to liberalism, orthodox Christianity often defined itself as “conservative.” Taken in this way it was “conserving” the historic, orthodox faith. Yes and amen.

But this move also had and has unfortunate consequences.

Left or Right?

Plotting itself on the horizontal axis of being to the “right” of the liberalism to its “left,” Christian faithfulness began to become defined by a location on that axis. But there are problems with using “conservative” as a term to describe faithful, historic, biblical Christianity.

One problem arises when someone defines faithful Christianity by where you stand on the left-right spectrum. Here someone can always outflank you on the right and claim to be “more faithful.” A rightward move groups anyone on the “left” as “unfaithful” or “less faithful” or “in danger.”

The political and cultural connotations of conservatism tie closely into this context. In fact, “conservative” primarily and historically has referred to movements in politics and culture. Conservative politics has desired incremental change to radical revolution, desiring to “conserve” the wisdom of the traditions of our forefathers. Similarly so cultural conservatism. So on the “left” is a radical revolution that wants to burn down the system and start over and on the “right” is a measured approach that wants to move more carefully. We can plot these ideas similarly. For example, in Lectures on Calvinism, Abraham Kuyper contrasts the leftist, liberalism of the French Revolution to the “rightist,” conservatism of the American Revolution.

Here’s where the rubber meets the road for us. The same word “conservative” is used for both political-cultural beliefs and theological ones, and all three have been mushed together. Theology, politics, and culture have so become conflated that a “conservative” Christian must be aligned on all three things to be considered a faithful Christian. So “conservative” has become synonymous with “orthodox” in a theological sense, but it then smuggles with it this whole political-cultural-theological trifecta. So we define “our team” by a location on the right-left spectrum, thinking anyone “to the right” (or left, in the case of liberals/progressives) is on “my team.” Now, mix in the shifting sands of what “conservative” means politically since 2016, and you’re in deep water.

Here, if someone doesn’t fall in line with the conservatism of the moment, politically or culturally, they’re branded a heretic theologically. Folks have so mushed together “conservative politics” with “conservative theology” that they often don’t have any category for someone who disagrees with them politically other than “liberal” or “heretic.” So in this view someone who doesn’t watch Tucker Carlson or who does read David French is compromised. We could illustrate approximately 14,765 other examples. When such a person sees political divergence, they only have the categories of error, heresy, drift, and so on to access. They then end up turning Christian brothers and sisters into enemies, because of the narrow way they define faithfulness. But, thankfully, the Christian theological tradition has a better way to talk about theological issues than the left-right axis of “conservative” and “liberal.”

Up or Down?

Rather than primarily viewing theology on the horizontal, left-right axis of conservative and liberal, we should plot theological beliefs on a vertical up-down axis. Here beliefs are not defined primarily by whether they are “conservative” or “liberal,” but by whether they are “orthodox” (up) or “suborthodox” (down). Orthodoxy is defined biblical and creedally, in the text of Scripture as faithfully defined, for example, in the Nicene Creed which summarizes the doctrine of the Trinity and the Chalcedonian Creed which summarizes the doctrine of Christ.

The vertical axis situates Christian theology uniquely compared to politics and culture. While our political and cultural views are important and (hopefully!) shaped by our theology, they are not identical to our theology. Here we must also acknowledge that there are political and cultural views that are certainly suborthodox, unbiblical and wrong. The problem is that these views don't cut neatly across partisan lines (for example, LGBT+ and abortion on the left and race on the right).

A More Accurate Way

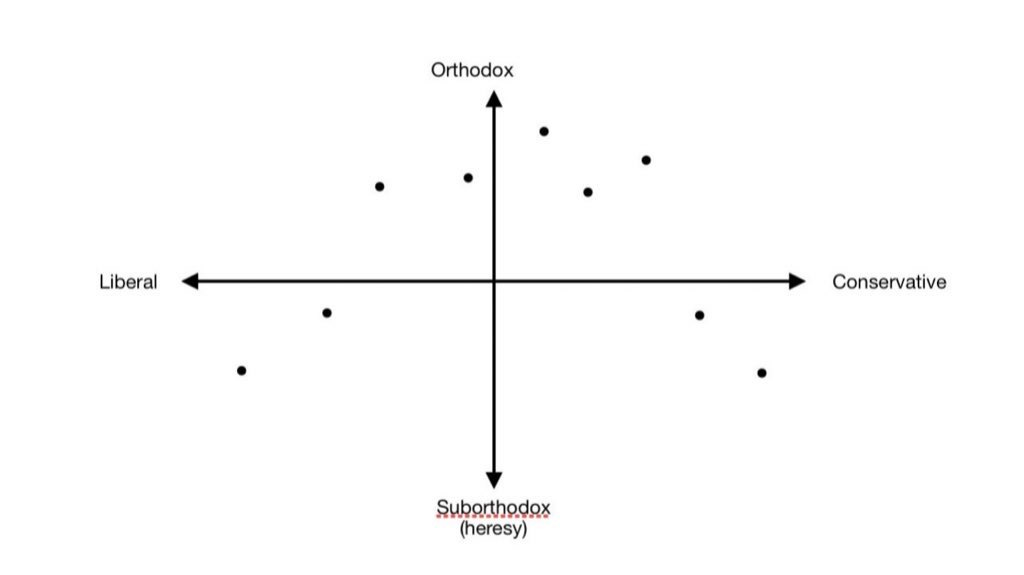

This moves us toward combining the horizontal/left-right axis and the vertical/up-down axis into a grid. Here we can plot both theological and political-cultural positions to give a more accurate view of a group’s or a person’s beliefs.

So a person might be at one point on the left-right axis but that doesn’t automatically define their position on the up-down axis.

Now, here is a hunch that I have. In our current cultural and political climate, I think the further you get to both the left and the right, the more unlikely you are to be “above the line” theologically. Anyone who has taken an intro to political science class has learned about the horseshoe theory of political ideology. That is, the extremes of left and right curve toward each other and basically mirror each other ideologically. This sort of maps onto the way I think the left-right (political) and up-down (theological) dynamics play out politically and theologically. Again, this is an educated hunch, based on the ways I’ve seen the extreme dynamics play out politically in recent years. (In other words, the dots are hypothetical and not based on actual data/persons. That said, I would put myself in the upper right quadrant, along with many folks I call friends and coworkers). The extreme views at the ends of the partisan spectrum have a “downward pull” on orthodox faith. Both extremes wind up worshipping the state, which can’t coexist with worship of God. We see this pattern in Daniel’s story, for example, and the repeated commands of pagan kings to worship them alone. As John Goldingay says in his commentary, “The false worship of the state abolishes the true worship of God by enforcing exclusive worship the state as embodied in the emperor.” In other words, you can’t serve Christ and Caesar, and no one can serve two masters. In other, other words, it’s hard for a hard-core partisan to enter the kingdom of heaven.

These thoughts for me are very much in process, as I’m trying to process the way recent years have rearranged things politically and theologically. As someone who has always considered myself a conservative both politically and theologically, I’ve been disoriented by the way words like “conservative” and “liberal” and “woke” have been lobbed and reshaped, and so quickly. At the very least, I hope this helps us think and talk more carefully about ourselves and others. I still sometimes use “conservative” as a shorthand, because I know that most folks still think in these terms. But I’m trying to increasingly use “orthodox” instead, because I think it’s the more accurate term. Let’s leave “conservative” for politics and give theology its rightfully unique place and terminology.

So, as I’ve said, this is still a series of ideas I’m whipping up, and this reflection has been me inviting you into the kitchen to tell me if it needs more salt or vinegar. What do you think?

I agree we can't link yourself to earthly views but to heavenly ones.

I like using orthodoxy instead of conservative- that’s a good distinction.